Antimicrobial resistance (AMR), a bigger threat than COVID19?

When we look back over the past year and half, we can see the impact and devastating consequences of not being able to control or treat a single virus. Now imagine the horror when we can’t even treat a ‘simple’ infection after we graze our knees or cut our finger in the kitchen. This is what is predicted as early as 2050 as a result of the growth of antimicrobial resistance (AMR).

As scientists, we are very aware of the coming storm, and it is now ranking higher and higher within governments strategic priorities, for example, the UK Government’s 20-year plan: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/antimicrobial-resistance-amr-information-and-resources.

Typically, when we think of AMR, we think it’s because of the misuse or overuse of antibiotics. But this combined with the lack of new antibiotics being discovered since the 1980s means we are rapidly heading towards a time where they become obsolete. Additionally, the more research undertaken, the more apparent it is becoming that antibiotics cannot be the sole cause of the global rise of AMR.

This is where I, as an environmental geochemist with an interest in remediation and industrial pollution, come in. With knowledge of co-selection and genetic mutations that can occur as a result of exposure to a chemically stressed environment, it seemed logical to start exploring this connection.

The sheer complexity of trying to connect biological, chemical and physical parameters within the environment is mind blowing.

This is exactly why, particularly with AMR research in its infancy, researchers focus their efforts on specific mechanisms. To date this is predominantly through clinical sampling but more recently has included looking at the waste streams of pharmaceutical treatment plants.

In 2017, I was lucky enough to work with a group that looked to explore the hypothesis of alternative causes of AMR in the environment (Rodgers et al., 2019). This was a Natural Environment Research Council funded project (NE/N019474/1) as part of ‘AMR in the real world’.

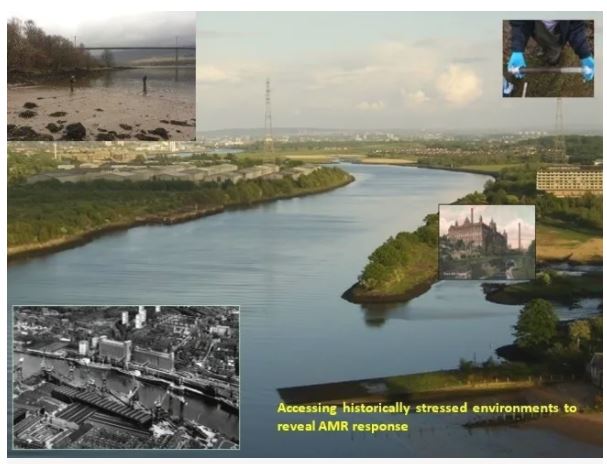

This study, led by the University of the West of Scotland, and in collaboration with Strathclyde University, looked at water and sediment samples along the River Clyde (Figure 1), Glasgow, Scotland. This area is known to be historically rife with industrial pollutants predominantly associated with shipbuilding and trans-Atlantic trading from the 19th Century to the mid-20th Century when industry in the region went into decline. We carried out a study where we compared levels of resistance genes at different locations and depths along the Clyde from Glasgow to Greenock and Helensburgh.

We found that there were correlations of resistance on a superficial level, with typical physicochemical properties, e.g. pH, Ec, OM, TOC, salinity etc. as well as key pollutants e.g. potentially toxic elements (PTEs) and polyaromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs).

The results of this study generated more questions than it did answers.

- Does the pollutant impact depend on the microbial community itself?

- Does the geochemical/natural parameters alter said microbial community, and is that what in turn caused the prevalence of resistance?

- Can a single species or geochemical variable be the root cause of resistance?

- Could geochemical parameters impact resistance alone, or is it their impact on the microbiome or specific species, which in turn caused AMR’s prevalence?

- How do we determine the most important variables that can be exploited for surveillance and/or remediation /control purposes?

A free-living amoeba – Acanthamoeba was identified as an ideal host that could be acting as a vector/carrier/prevailer of AMR as hypothesised in figure 2.

Several species of Acanthamoeba were found at the majority of River Clyde sample sites.

Having identified these species it is now important to assess the role they play in the spread of AMR within their ecosystem

In parallel I believe it is fundamental to try and identify as many different environmental conditions as we can and evaluate potential links to AMR, Acanthamoeba and other key protists. To achieve such a large undertaking, I hope to start a wide-scale process of sample collections from as many geographical locations and environmental conditions as possible.

Currently, I’m just starting a 3-year PostDoc on a UKRI Natural Environment Research Council funded project (NE/T012986/1), led by UWS and working with partners in India. This project will focus on the biological and chemical compositions of common effluent waste treatment plant and assess its impact on antimicrobial resistance.

In order to expand on current understandings, my next steps will be a pilot study requesting samples from different matrices (water, soils, sediments and slurries), in rural and urban areas, agricultural and industrial settings, from all over the world. By characterising these samples, and seeing if we can isolate Acanthamoeba, I hope to determine links with the surrounding environmental and biological ecosystems.

Rodgers, K. et al. (2019) ‘Can the legacy of industrial pollution influence antimicrobial resistance in estuarine sediments?’, Environmental Chemistry Letters, 17(2), pp. 595–607. doi: 10.1007/s10311-018-0791-y.